Growing Under Pressure: A Thai School

Learning How to Prosper While being Different

Paron Isarasena, paroni@cscoms.com

Darunsikkhalai School for Innovative

Learning, Bangkok, Thailand

Nalin Tutiyaphuengprasert, Nalin.tut@kmutt.ac.th

Darunsikkhalai School for Innovative

Learning, Bangkok, Thailand

Arnan Sipitakiat, arnans@eng.cmu.ac.th

Department of Computer Engineering,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Abstract

This paper describes the evolution over

the past decade of the Darunsikkhalai School for Innovative Learning (DSIL) near

Bangkok, Thailand. Established as a constructionist school, DSIL aims to be a

concrete model for Thailand to better develop its educational system. Daring to

be drastically different from conventional schools, DSIL had to endure immense

pressure from concerned parents and authorities. In order to sustain, DSIL

adopted the principle of organizational learning. This approach allowed DSIL to

evolve and carry on while still maintaining its core values. Key aspects of

such process are described to show how the school managed to respond to

scepticisms regarding curricular content and assessment.

Keywords

School, Learning Organization,

Curriculum and Assessment

A School that Nobody Understands

When DSIL was established in 2000, there

were less than ten schools in the whole country that were considered

“progressive”. Even with that small number, progressive was used conservatively.

Therefore, DSIL was something drastically different from what Thailand, and

perhaps most anywhere, is used to. At the time, the Suksaphat Foundation, the

school’s founding organization, had worked with professor Papert and his team

at the Epistemology and Learning Group at MIT for four years trying to seed

changes in Thailand’s rigid learning system. Disappointed by the resistance to

change (Papert, 1997) and failed collaborations, the foundation decided it

needed to create a new learning space from the ground up that can be a

Constructionist school from day one.

The Suksaphat Foundation is funded and run

primarily by the private sector that came together realizing that the ability

to learn is key to the country’s competency in the modern world. Thus, Papert’s

vision about “learning how to learn” resonated well and has made

Constructionism (Papert & Herel, 1991) the foundation’s main guiding principle. Schools, at least at the

time, did not share this same ideology. DSIL’s approach towards learning such

as no grade levels, student-driven long-term projects, relatively very little

“teaching”, was highly questioned. The initial thirty students belonged to parents

who were either business owners or were highly educated—the minority of parents

who can foresee the potential benefits of DSIL over the traditional education. Also,

many made their final choice based on the good name of the foundation. More than a decade has passed. DSIL now has seventy seven students

ranging from primary to high school levels. DSIL is still drastically different

from other common schools but the perception is much more positive.

The main focus of this paper is based on

the fact that DSIL did not start off knowing exactly what to do.

Constructionism was a guiding principle, but translating it into day-to-day actions

was extremely challenging. With only four years working with Papert and zero

experience in running a real school, DSIL had a great deal to learn as an

organization. The greatest challenge was how to keep the school adaptive while

not being neutralized by the pressure from the traditional school system.

A School that Learns

DSIL has a culture of accepting change. It

uses “learning” as means for a sustainable development of the school. As an

official member in the Society for Organizational Learning (SOL), DSIL has

adopted a “Learning Organization” model. Founded by Peter Senge from MIT’s

Center for Organizational Learning, SOL is a not-for-profit organization that

focuses on the development of people and their institutions. By being part of

SOL, the school was able to adopt useful principles to help govern the

organizational learning process. Teachers (or more commonly referred to as

“facilitators”) participate in daily and weekly meetings to discuss and reflect

upon their actions. The discussions are guided by the following Learning

Organization Disciplines (Senge et al, 2000).

1. Personal

mastery: Facilitators set their own goal of how

they want to improve themselves. The meetings allow them to reflect on where

they are and how to fulfil their goal.

2. Mental

models: Facilitators are encouraged to be

open-minded, ready to accept and learn from each other, and develop trust in

each and every member of the organization.

3. Systems

thinking: Understanding the structure of a system

enables more effective planning and problem solving. It enables the facilitators,

staff, and students to work together to “see” the causes, develop, and test

solutions.

4. Shared

vision: The vision and strategy of the school is

shared and anybody can participate in the development or refinement of such

goals.

5. Team

learning: DSIL has a strong culture of sharing and

collaborating. Every member participates in a “show and share” session, which

allows teams to emerge to either solve problems or branch off into new

directions.

Results

The following are some results that

illustrate how DSIL has evolved and sustained itself.

Learning at DSIL

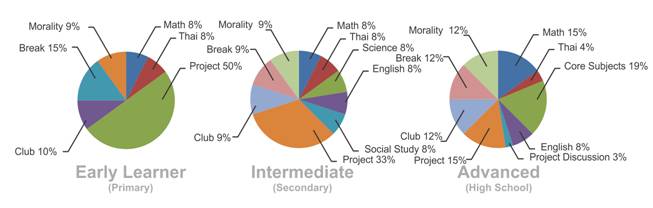

Students at DSIL, especially at the primary

level, spend a great deal of their time working on projects that were initiated

together between the teachers and students (see Figure 1). The projects are

closely monitored and guided by the teachers. The teacher to student ratio is

approximately 1:2.5, which has remained the same since the early years (12

teachers and 30 students in 2001 compared to 31 teachers and 77 students in

2011). The idea of reducing the number of teachers often come up especially

during financial difficulties, but the school as a whole (school managers,

teachers, and others who are involved) decided that it is more important to

keep the level of support students receive.

After the initial six years when students

at DSIL started secondary school, there were more pressure from parents

concerning whether their child could perform well at the national tests. A

project based learning approach did not give the level of assurance many

parents needed. This concern caused fear that did not exist in the primary

level. Every year, a significant number of parents relocated their child to

other schools because of this reason.

Driven by this concern, DSIL had to adapt

in order to build up trust. The school established a special session to help

students master the materials needed for the exams while still spending a

significant amount of time working on projects. Figure 1 shows how high school

level students allocate a fifth of their time, most of which used to be project

time, to study the core subjects needed for the exams. The important point here

is that this decision was not made by an individual; it was decided by the

school community. Students were part of the discussion and they together

decided on what to do. This is an important example of the value of a learning

organization. Everybody understood and felt ownership over the decision. We

believe that this ownership has made DSIL students perform well (see next

section) at the national tests while still spending time on project-based

learning.

Figure 1. The average time

allocated to different activities based on a 40 hours per week period.

Assessment and National Tests

One of the first challenges of DSIL was to

figure out how to satisfy the national curriculum while being a

project-oriented school. DSIL could lose its school credentials if it cannot

cover all the curricular subjects. This issue was managed by adopting a

curricular mapping scheme. Every project was dissected and each component mapped

to items in the curriculum. The school has developed a tracking system where

this information can be entered and tracked on-line by teachers and parents

(See figure 2). The system was used in the self-evaluation process by students

where they can then discuss the necessity to study or organize projects to

cover the missing parts in their portfolio.

Figure2. An online tracking

system helps teachers, parents, and students to evaluate their progress towards

fulfilling the curricular subjects mandated by the Thai school system.

In the recent years, when the first batch

of students are nearing their high school graduation, DSIL had to prove to

parents that it can do well at the national test. Thailand is known for having

one of the world’s largest tutoring industries. How can a school perform well

if it spends only a fraction of its time on exam preparation? It turns out that

DSIL students can manage the exams well. Figure 3 shows that the scores are all

above the average. The school ranked 3rd place in the regional

district in 2010. Although DSIL values other deeper aspects of learning than that

offered in test scores, this outcome demonstrates that a constructionist school

can perform well in the traditional system.

Figure3. Graphs showing how

DSIL students have been able to perform well at the national tests.

Public Acceptance

DSIL’s twelve year existence is, by itself,

a proof that it is not just a short-lived experimental school. DSIL has

benefited from the increase in the public’s awareness of alternative education

driven by the educational act established in 1999. The act shared many values

with DSIL and has created a stir in the school system. Although the educational

act is arguably a failure in practice, but what goes on in DSIL became more

familiar to the general public. Moreover, now that there is some evidence that

student can perform well at the national tests, the stress has eased. However,

the shift is still not strong enough for most parents. The enrolled students

remain children of parents who either own a business or have gone to graduate

schools as shown in Table 1.

Year |

% Parent owning a business |

% Parents with graduate degrees |

2001 |

62.5 |

35.7 |

2012 |

77.3 |

40.9 |

Table 1. Parent profile in 2001 compared to 2012

remains similar

Expansion

DSIL remains a drastically different school. There have

been five other schools that have adopted parts of DSIL’s approach in the past

five years but they are not at an organizational level. A rather surprising

impact, though, is in the private sector. Through the Suksaphat foundation,

many large cooperations such as the Siam Cement Group, Petroleum Authority of

Thailand, and Bangkok Bank have become interested in the learning methodologies

at DSIL. A number of courses are now being offered to company employees and are

popular as means for human resource development. These courses often include

DSIL students acting as facilitators. DSIL perceives this interest as an

indication that it is developing the right skills needed in today’s competitive

world.

Conclusions

This paper has described how a

constructionist school has been able to grow under immense pressure from

parents and the traditional education system. The possibility of parents

withdrawing their child has been the greatest threat. Being able to learn and

constantly adapt to the situation at hand was key. Through this process, DSIL

has proved that it is possible to focus on “learning how to learn”, while being

able to help students fulfil the expectations of the traditional system.

References

Papert, S., Harel, I. (1991).

Situating Constructionism. In I. Harel & S. Papert (Eds.), Constructionism (pp. 518). Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

Papert, S. (1997). Why school reform

is impossible. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 6(4), 417-

427.

Senge, P., Cambron-McCabe, N., Lucas,

T., Smith, B., Dutton, J., & Kleiner, A. (2000). Schools that learn: A

fifth discipline fieldbook for educators, parents, and everyone who cares about

education. New York: Doubleday.