Preparing Teachers to Use Laptops

Integrated to Curriculum Activities: the experience of One Laptop per Student

project at Unicamp

José Armando Valente jvalente@unicamp.br

Department of Multimeios, NIED –

UNICAMP and CED-PUCSP.

Maria Cecília Martins cmartins@unicamp.br

Nucleus of Informatics Applied to

Education (NIED) – UNICAMP

Abstract

The objective of this paper is to

describe the process of preparing teachers at schools that are receiving the

educational laptops (also known as the US$100 laptops) as part of the One

Laptop per Student Project, developed by the Ministry of Education in Brazil.

The article describes the structure of

the training plan which is being implemented and, specifically, the training of

teachers from four schools in the state of São Paulo. Teacher training

at these schools is under the responsibility of Universidade

Estadual de Campinas (State University of Campinas - Unicamp). These teachers are gradually appropriating the laptop resources and

as part of their training, are working with students using laptops in the

classroom and in different school spaces, and exploring different school

curricula.

Keywords

Project UCA, one laptop per student, educational

laptops, teacher training, Unicamp

Introduction

In 1968 Alan Kay presented an idea that

seemed impossible: every child should have his/her own computer. Kay put

forward this idea right after having visited Seymour Papert at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), who was beginning his work with

Logo. Kay was impressed by the fact that the children were using the computer

to solve complex mathematical problems, and understood that every child should

have his/her own portable computer.

The idea of the portable computer became

concrete in 1972 with the Dynabook, which was developed by the Learning

Research Group (LRG). Kay created the LRG as part of the Xerox Park laboratory

(Kay, 1975). The Dynabook can be considered one of the precursors of current

laptops. According to Kay’s conception, this tool should be a portable computer

that is interactive and personal, and as accessible as books. It should be

connected to a network and offer the users word-processing, images, audio, and

animation. Laptops today have all the characteristics described in Kay’s

vision.

The idea that every child should have

his/her own computer became real in 1989 when the Methodist Ladies’ College in

Melbourne, Australia proposed that every child in 5th grade should have

his/her own personal computer. This experience extended to the other grades

until all the students from 5th to 12th grade had their

own laptops (Johnstone, 2003). The “P” in the term “PC – Personal Computer” was

taken seriously, and the computers were literally personal (Sager, 2003). Since

2001 many schools and educational institutions in the United States of America

have implemented the one laptop per child – known as 1-1 laptop, or 1-1

computing.

The arguments used to justify the 1-1

scenario, in general, consider improvements in the student’s behavior and

disciplinary issues, performance on national or international assessments,

social inclusion of students who are socioeconomically disfavored, and

preparation for the work force.

However, the ideas Kay developed concerning

learning environments are in fact not yet being implemented; much to the

contrary. As noted by Kay, the way in which, for example, science is treated in

school has nothing to do with doing science. The student does not have the opportunity

to deal with uncertainties, to question, and to work with incomplete or

imprecise models; challenges that can be debugged with the help of

technologies, classmates, teachers, and specialists (The Book and the Computer,

2002). In general, computers are used to access already confirmed facts, and to

replicate much of what already happens with a pencil and paper. This can be

seen in many of the studies that discuss implementing laptops in schools.

The UCA Project (Um Computador

por Aluno or One Computer per Student) being implemented by the Ministério

da Educação (Ministry of Education - MEC) in Brazil

envisions, amongst the changes that will take place when implement this

technology in schools, a change in the way in which curricula is approached in

the classroom. This does not mean a change in the curricula itself or a change

in the content; rather, this new pedagogical approach considers the possibility

of the student experiencing the ideas presented by Kay. For example, the

student would do science rather than study accumulated knowledge in the field

of science. However, as Kay already mentioned, the simple presence of

technologies does not guarantee the necessary and desired pedagogical changes.

In addition to the presence of the technology, it is necessary to train

teachers so that they are able to integrate laptops into their curricular

activities.

The Journal of Technology, Learning, and

Assessment dedicated the entire January 2010 issue to the theme of the use

of laptops in a 1-1 situation (JTLA, 2010). Other works try to synthesize the

results of various articles published on the subject (Penuel, 2006). The

results in the different experiences described are not 100% favorable: some

aspects of the projects present considerable gains, while as other aspects of

the use of laptops in a 1-1 situation do not bring about significant

improvements.

However, it is important to note that

teachers are mentioned in practically all of the studies as having a

fundamental role in the implementation of laptops in schools. For this to

happen, teachers must receive training on how to use the laptops, on how to

develop learning projects that are centered on the student, to become better

prepared to help students, and on how to create a learning environment that is

favorable to the use of this technology.

A positive aspect is that if this training

is effective, impacts become apparent in different situations. Those teachers

who are better prepared may come to view the laptops’ use in a more favorable

light. The teachers also become more able to track the students’ progress, and

understand how students apply curricular content to problem solving situations

(Penuel, 2006; Windschitl & Sahl, 2002).

Therefore, the objective of this article is

to present and discuss how teacher training is taking place in the schools

affiliated to the UCA Project. This training is under the responsibility

of Universidade Estadual de Campinas (State University of Campinas - Unicamp).

Our aim is to discuss the structure created for this training, and how the

teachers are working with both the researchers from Unicamp and their own

students in the classrooms. The following sections provide a brief description

of the UCA Project, the methodologies used to train teachers in the

schools affiliated to the UCA-Unicamp Project, and the results of this

training. The latter is done through a discussion about the ways in which

teachers have implemented the laptops in their own classrooms.

The “Um Computador por Aluno – UCA”

Project

The UCA Project anticipates the

deployment of educational laptops in schools, as well as a preparation of

teachers and administrators for the use of this equipment with students during

educational activities. This is a pilot initiative developed by the MEC in

2010 to be under the responsibility of the Secretaria de

Educação a Distância (Secretariat for Distance Education

- SEED). With the extinction of SEED, in 2011 the Project was

transferred to the Secretaria de Educação Básica (Secretariat

of Basic Education - SEB).

The UCA Project’s objective is to

promote an improvement in the quality of education, digital inclusion, and the

Brazilian computer industry’s participation in the development and maintenance

of the equipment. Considering the work that had been taking place in the field

of the use of technology in education, particularly the work being done with

desktops in school informatics labs, the UCA Project is innovative in

many ways. For example: the use of the laptop by all the students and educators

in public schools in a context of immersion into the digital culture; the

mobility to use the equipment in other environments inside and outside of the

school; the connectivity by which the laptops can be used for teachers and

students to interact by means of the wireless Internet connection; and the

pedagogic use of the different medias available in the educational laptops.

The UCA Project was conceived by a

group of technicians from SEED and the Grupo de Trabalho UCA (UCA

Work Group - GTUCA), which is made up of research specialists in the

area of the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in education

from the following universities: UFRGS, USP, UNICAMP, PUCSP, PUCMG, UFRJ, UFSE,

UFC, UFPe. These universities are called Instituições de

Educação Superior Globais (Global Institutions of Higher

Education - IES Globais). The GTUCA participants developed the

document with UCA Project Objectives (Princípios, 2007). GTUCA was then subdivided into three working groups responsible for the

development of the following three documents respectively: Development and

Monitoring, Evaluation, and Research.

The process for implementing the UCA Project

began with the purchasing of 150,000 laptops in 2007. This purchase was made

through a national bidding, where the winner was the ClassMate brand laptop,

developed by Intel and produced by a Brazilian company.

Approximately a total of 350 schools were

selected, and these are spread out amongst the 27 States. Roughly 10 schools

were selected per State: 5 municipal schools, selected by the União

Nacional dos Dirigentes Municipais de Educação (National

Union of Municipal Education Leaders – UNDIME); and 5 State schools,

selected by the respective Secretarias de Educação Estadual (Secretariats

of State Education). In six municipalities (Barra dos

Coqueiros/SE, Caetés/PE, Santa Cecília do Pavão/PR,

São João da Ponta/PA, Terenos/MS, and Tiradentes/MG) the

UCA-Total was implemented, in which all of the schools in each of these

municipalities become part of the UCA Project. The 350 schools were

selected with the intent of complementing different types, such as urban,

rural, indigenous, and etc. Each school could have no more than 500 students

and teachers. The MEC delivered laptops and a server to each school, and

each school was then responsible for providing infrastructure such as space,

electricity, internet, and closets for storing the equipment and charging their

batteries.

Teacher and administrator development was

based on the proposal “Formação Brasil” (Brazil Training),

elaborated by the GTUCA subgroup Development and Monitoring. In order

for this training proposal to be implemented a network of universities and Núcleo

de Technologia Educacional (Education Technology Nuclei - NTE) was

created in each State. Global IES created teams of researchers and

interns on fellowships from the SEB/MEC to be responsible for the

preparation of local training teams, which were in turn responsible for

implementing teacher and administrator training at the schools. The training

teams were made up of researches from the State’s universities (IES Locais; Local IES), professors at the respective Secretariats of Education, and NTE.

The local training teams are responsible for teacher and administrator training

at the 10 schools in the UCA Project in each State, including those with

UCA-Total. Another form of participation anticipated for the training process

was that of student-monitors or interns, who would be prepared to give

technical support to the teachers at the schools.

Methodology used for the teacher training

in schools affiliated to the UCA-Unicamp Project

The activities of the UCA Project

that took place in 2010 and 2011 had the objective of implementing the Project

in the schools, and training teachers and administrators in the schools to use

educational laptops with students during activities for learning and teaching

(Projeto UCA-Unicamp, 2010).

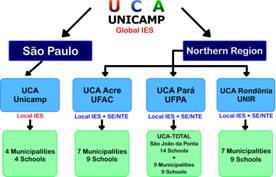

The UCA-Unicamp Project corresponds

to the UCA actions developed under Unicamp’s supervision in three

Brazilian States in the Northern Region of Brazil (Acre, Rondônia, and

Pará), and in four municipal schools in the State of São Paulo,

as described in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

UCA-Unicamp Project Structure: states, universities, municipalities, and

schools involved

As seen in Figure 1, the UCA-Unicamp

Project is acting in schools in the State of São Paulo, and in

universities in the Northern Region of Brazil, in the States of Acre (AC),

Rondônia (RO), and Pará (PA). It carries out activities with teams

at local universities – UFAC, UNIR, UFPA – which are responsible for the UCA Project activities in their respective States. These universities, in

partnership with Municipal or State Technology Nucleuses and Secretariats,

carried out the implementation of the UCA Project in schools, as well as

teacher and administrator training. In this article we will highlight some of

the activities and results obtained in the UCA-Unicamp context of the

State of São Paulo.

The UCA-Unicamp team is comprised of

researchers, trainers, and tutors. In the State of São Paulo the UCA-Unicamp

carried out activities with 4 local teams responsible for applying the teacher

and administrator training at the following schools and municipalities: EMEF

Prof. Jamil Pedro Sawaya (São Paulo), EMEF Profª Elza M. Pellegrini

de Aguiar (Campinas), EMEF Dr. Airton Policarpo (Pedreira), and EMEF

José Benigo Gomes (Sud Mennucci). These schools correspond to a population

of about 1503 students and 130 teachers.

In 2010, when the equipment and

infrastructure provided by the UCA Project became available, the process

of implementing the program in the schools began. This reality demanded a large

interaction between the various teams (MEC, University, secretariats,

schools) providing information and support to each school so that they could

make decisions. During the second semester of 2010, with a few operational and

infrastructural issues having been solved, teacher and administrator

development sessions, as well as activities using educational laptops with

students, took place. The first meetings involved administrators and teachers

at the school, and, gradually, the teachers began to work with the students as

part of their training process.

The “Formação Brasil” course

has five modules of a cumulative total of 180 hours that should take place in a

blended manner. The face-to-face activities in the course were scheduled to

take place at the school. These involved activities where the teachers were

working directly with the students using laptops in the classroom. The

activities that took place at a distance, through the virtual environment e-Proinfo,

anticipated an exchange of experiences by the teachers, where they would share

reflections, uncertainties, questions, and debates about their experiences

while using the laptops with their students, as well as while studying the

theoretical principles involved in using technologies during the processes of

teaching and learning.

In general terms, each module encompassed

certain content that give direction to the practices teachers and

administrators use in schools. These included, for example: the appropriation

of technological resources available on the laptop; the use of applications

available on the laptops and on the Internet with the intent of integrating

these resources into curricular content; the issues related to the

administration of ICT within the school’s structure; the pedagogy that should

be applied in projects that contemplate the specificities of disciplinary and

interdisciplinary knowledge; and the last module geared towards elaborating a Projeto

de Gestão Integrado com Tecnologia (Management Project Integrating Technologies - ProGITEC)

for the following school year in each school. The creation of the ProGITEC

demands a delineation of guidelines for the use of the laptop in the school,

thus encouraging teachers and administrators to make explicit their

conceptions, proposals, and discussions regarding the strategies for using the

educational laptops in a way that is aligned to the Pedagogical Political Plan

of the school.

The local training

teams should have adjusted the training proposal made by the UCA Project,

thus allowing for accommodations that take into consideration the real contexts

and conditions of each school at the moment when the training was taking place.

Therefore, each training team selected from the training modules content,

supporting materials, and activities that were most relevant to the school’s

context, and added other elements to the training, thus adjusting the training

so that it best meet the needs of each group of teachers and administrators.

Results of

the training activities in four UCA-Unicamp schools

To exemplify the work dynamic as well as some of the

results obtained, we will, in this article, focus on the training and

monitoring that took place by the team at Unicamp together with the four

training teams at the municipal schools of São Paulo, Campinas,

Pedreira, and Sud Mennucci. Between June and December of 2010 five meetings

took place with the local teams at these four municipalities with the objective

of orienting and promoting an exchange of ideas amongst the teachers and

administrators at the four schools. The meetings would assist each team in the

process of developing training actions.

The training activities in the schools took place between

August and December of 2010, and, throughout the year of 2011, also involved

the inclusion of topics from the “Formação Brasil” Course.

In November of 2010 the activities for the use of laptops in the classroom

began, thus favoring an association between theory and practice. During the

year of 2011 the training activities were resumed, and the teachers carried out

activities that related to the five modules in “Formação

Brasil.” Part of these activities took place in the classroom with their

own students. This training work took place at the school. Each school relied

of the supervision of one researcher from the UCA-Unicamp team that

monitored the teacher trainings, and assisted the teachers with the activities

related to the topics discussed in the five modules, as well as with the actual

use of the laptops in the classroom.

The training sessions in the schools took place weekly and

each lasted for an hour. Activities that took place at a distance also

complemented this training, and were implemented with the help of the e-Proinfo virtual environment. As the teachers, initially, did not have any experience

using distance education environments the e-Proinfo tool was introduced

slowly.

When the UCA Project was initially implemented in

the schools, one of the challenges faced relates to the teachers’ insecurity

towards using the educational laptop. The equipment was new, and its use in the

classroom by students was an unknown for both the teachers and the

administrators. The initial challenges related to classroom management, and to

the use of the equipment by the students. These insecurities were frequently

manifested in the training sessions, as can be seen in the following testimony:

Z.A.B.S. – Pedreira,SP: I feel

insecure. I don’t know how it is going to be with all the students manipulating

the computers at the same time; what if we have a problem, how will I solve it?

Will I be able to handle this?

G.T. – Pedreira, SP: I am very

anxious, this is a new project that will give the students many opportunities.

However, at the same time I am apprehensive about not knowing how to use the

laptop.

During the initial months of the training it was

possible to observe a progressive involvement of the teachers and

administrators in the activities, thus improving how they used the equipment, e-Proinfo,

and the Internet. The initial resistance and uncertainty were slowly

substituted by a desire to overcome their own personal challenges appropriating

the technology. Gradually, rooted by the practical context and exchange of

ideas, the teachers began to catch a glimpse of the possibilities of using the

educational laptop in their classroom. It is important to note that the initial

challenges faced by the teachers were circumvented by the constant acting upon

by the professionals at the school (colleagues, administrators, and

technicians), who addressed or passed on the questions, and encouraged the

teachers. From a technical-pedagogical standpoint, the constant support given

by the researcher from Unicamp to the teacher, both regarding the use of the

educational laptop and the implementation of the from-a-distance training

sessions, was a differential that rooted the engagement of the teachers in the

project. This created a space where the teachers accepted the challenge of using

the educational laptop in the classroom with their students. Therefore, with

time, one can observe that the school teams became more fluent and secure,

which influences their motivation to use the laptops with the students. During

this process we noted that strategies for using the technology daily in the

school’s context began to appear, as expressed by one of the teachers at one of

the schools:

E.A.F. – Pedreira: Dear UCA

colleagues. (05.11.2010). We began to use the laptops with our students, simply

an activity for them to explore the Classmate. We have worked in 9 classrooms

so far, we are working in stages because the closets are not ready yet, we are

charging the laptops’ batteries in the informatics laboratory using the

stabilizer, 15 laptops at a time, and it is working. The children are

fascinated, not to mention the students’ abilities. It is a success. Hugs to

all!

In the report above, we observe that the process for using

the laptops with the students takes place incrementally. The initial activities

involved a free exploration of the laptops within the classroom. Some

technical-operational strategies were planned to make this activity feasible,

such as: scheduling time to use the equipment (due to the need to charge the

laptops’ batteries), and the support from other people (such as administrators

and technology technicians). Such demands were a result of the teachers’

initial predictions about what it would be like to manage a classroom where

each student had his/her laptop; and predictions about the challenges students

would face when using the laptop (due to their young age or lack of experience

using computers). Figure 2 shows the use of laptops in the classroom, where one

can see the students working in groups and individually, and the teacher provides

guidance to the students.

Figure

2: First activities using the laptops with students from the school in the city

of Pedreira.

Opposite to some of the predictions expressed by

the teachers during some of the initial training sessions, these initial

experiences with the laptops in the classroom allowed for some satisfactory

results: the students handled the laptop with ease, helped each other, and

focused on the activity and exploration of the equipment, as observed by some

of the teachers.

M.L.G. – Pedreira, SP: .. The

students made us surprised, we did not have any challenges during this class,

they only asked for me to check on their work all at the same time to make sure

they were doing the right thing.

A.C.S. – Campinas, SP: The students’

first contacts with the laptop gave the teachers more confidence, they

understood that the students “treat” the equipment with composure, they

interact amongst themselves sharing their discoveries, and deal with problems

with the equipment in a natural way

The teacher’s accounts of success throughout the time when

the first experiences with the laptops were taking place, made the other

teachers calmer, thus creating an environment of greater security, which is

important for the success of this stage, as well as continuity of the project.

The next step in the training was the creation and

implementation of scenarios for the laptops’ use with the students, in a way

that would align with curricular content. This factor, during the initial

stages of the training, seemed like a huge challenge. In order to start this

new phase, for example, the teachers at the municipality of Pedreira elaborated

lesson plans that had specific themes to be address, specific dynamics, and the

specific resources on the laptops that would be needed. These plans were

created individually or in groups. Some teachers who work with a same

grade-level, for example, preferred to create a common lesson plan, as seen in

Table 1. In this table one can observe the theme for the project, the

anticipated learning objective, the resources needed, and the grade involved.

Lesson Theme |

Learning Objectives |

Resources |

Grade / Year |

Poetry by

Cecília Meirelles |

“Leilão de

Jardim” (Garden Auction)

Recognizing letters

(by finding them on the educational laptop’s keyboard).

Manifesting

creativity (illustrating a section).

Improving the ability

to understand poetry. |

Tux Paint

(word processing and stamps) |

1st grade |

Animals in the Pantanal |

Activities that

relate the laptop to “Reading and Writing”

Searching for

information about a few animals that live in the Pantanal.

Organizing

information in into taxonomy cards (found in the textbook)

Collaboration

(partnerships) |

Internet

Books “Ler e Escrever” (Reading and Writing) |

2nd grade

3rd year |

Creating Stories with Fables |

Gathering information

(interviewing family members), reading and writing essays, working within the

genre of fables. |

Internet

Kword

Tux Paint

Projector Multimedia |

3rd grade

4th year |

Pedreira, Porcelain Flowers |

History of the city,

tourist points, economic sectors, political sectors, educational sectors,

cultural sectors, and geographic locations.

Production of an

essay based on the information found on the Internet. |

Internet

Kword |

4th grade

5th year |

Table 1: Synthesis

of a few lesson plans developed for the use of laptops to address curricular

content.

The testimonies below express some of the important aspects

of the training courses for the teacher: incentives for the appropriation of

technologies by the teacher; experiencing new pedagogical possibilities

together with the students; development of work in groups and spaces for

exchanges of knowledge amongst the students; proposals for articulate projects

with technological possibilities; and practical activities for the use of

technology to help teachers reflect on their pedagogical work.

Teacher C – Pedreria, SP: I believe it was

a continuous process, for everything we learned throughout the course made us

reconsider our pedagogical practices in order to insert the computer so as to

improve the students’ learning, in addition to providing us with an incentive

to get to know this virtual world.

S. R. M. G. – Sud Mennucci: It was gratifying to

create moments that were relaxed and meaningful for the students, for, using

the technological tool, we were able to create a project as a team in which the

students behaved very well, and did not hesitate to help their classmates solve

any questions regarding the use of the technology.

It is still not possible

to identify significant pedagogical changes, considering the time in which the UCA Project has been implemented in the four schools. However, we have observed

that the teachers, in a general sense, have already adopted a new attitude

towards their work. There are various indications that important pedagogical

changes might take place, changes which demand time and new experiences in

order to become concrete. The teachers incorporate new learning spaces, work

dynamics, reflect with partners in order to elaborate projects, and exchange

strategies. Thus, it is possible to note that there is a general mobilization

in order to increment scenarios for teaching and learning. These include: use

of the laptops by teachers and students in the school creating an environment

of digital inclusion; pedagogical use of different medias available on the

educational laptop; connectivity – use of the wireless networks connected to

the Internet – allowing for communication and interactions between the students

and the teachers; and the mobility to use the equipment in other environments

inside and outside of the school. Figure 3 illustrates some of the students

using the laptops in the library, in the patio, and carrying out different

activities related to the scenario of “social entrepreneurship” taking place

within the school.

Figure 3: Dynamics of the use of the laptops in the

School José Benigo Gomes, Sud Mennucci, SP

Such dynamics show that activities related

to the use of the laptops are no longer restricted to the classroom. Students

can be actively engaged in their class-work or pedagogical activities even

while not in the classroom or under the teacher’s supervision. One of the

benefits teachers noted is that schoolwork is now productive, while as before

it was restricted to the classroom. Now, schoolwork and pedagogical activities

take place anywhere and at any time, and are no longer limited to the confines

of the classroom or the class-period.

Conclusions

The educational laptops (also known as US$100

laptops) are beginning to become part of the reality of some Brazilian schools,

thanks to the UCA Project, developed by the MEC. However, simply

installing these laptops in the schools does not mean that they will become a

part of curricular activities. For this to happen, it is important to train

teachers and administrators in the schools so that they can implement the

necessary changes in different aspects of the educational process, such as the

school’s space, the class period, as well as curricular activities.

In Brazil, training of teachers and

administrators from the schools that are receiving the laptops is being carried

out by universities whose representatives participate in a MEC advisory

committee for the implementation of the UCA Project, called Global

IES. In the case of UCA-Unicamp, we interact with universities in

the State of Acre, Pará, and Rondônia that work directly with

local schools that are part of the UCA Project. We are also responsible

for training teachers in the four schools participating in the UCA Project

in the State of São Paulo. For the purpose of this article, we described

the teaching training process taking place in four schools in the State of

São Paulo.

The results obtained up to the present

moment indicate that the teachers are gradually appropriating the laptops as a

resource, and, as this takes place, start to use the laptops with their

students for activities taking place within the classroom. These experiences

with technology within the classroom are still isolated and, up to this point,

were part of the activities done during the training process. In addition,

teachers have begun to see the laptops’ potentials, and understand the

different resources that can be used in activities taking place in varying

learning spaces within the school or used to explore different curricular

content. It is still early to describe the benefits of the use of the laptop

for the students themselves. However, there is great enthusiasm on the part of

the students, which has been transmitted to the teachers and administrators,

thus creating an educational environment where teachers are collaborating, and

establishing partnerships with the students. To experience this enthusiasm and

to be able to channel it towards pedagogical issues is, in and of itself, a

great accomplishment. We hope that these are the first steps towards more

profound changes that could take place in schools, and that, through these, we

are able to achieve the UCA Project’s objectives of improving the

quality of education, and of promoting the digital inclusion of students within

the school context.

Acknowledgements

This work is

support by Secretaria de

Educação Básica (Secretariat of Basic Education - SEB)

Ministry of Education, and a grant 306416/2007-7 from Conselho Nacional de

Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico,(National Council for Scientific and Technological

Development - CNPq), Brazil.

References

Johnstone, B.

(2003) Never Mind the Laptops: kids, computers, and the transformation of

learning. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse Inc.

JTLA (2010). The

Journal of Technology, Learning and Assessment. Available in:

http://escholarship.bc.edu/jtla/. Accessed in: March 2012.

Kay, A. (1975).

Personal Computing. 1975. Available in: http://www.mprove.de/diplom/gui/Kay75.pdf.

Accessed in February 2010.

Kongshem, L.

(2003). Face to Face: Alan Kay Still waiting for the Revolution. Scholastic

Administrator. Available in: http://content.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=5.

Accessed in: March 2012.

Penuel, W.R.

(2006). Implementation and effects of one-to-one computing initiatives: A

research synthesis. Journal of Research on

Technology in Education, 38(3), 329-348.

Princípios

(2007). Princípios Orientadores para o uso pedagógico do laptop

na educação escolar. Non published

document.

Stager G. (2003). School Laptops -

Reinventing the Slate. Available in: http://www.stager.org/articles/reinventingtheslate.html.

Accessed in: March 2012.

The Book and the Computer (2002). The

Dynabook Revisited - A Conversation with Alan Kay. Available in: www.squeakland.org/content/articles/attach/dynabook_revisited.pdf.

Accessed in: March 2012.

UCA-Unicamp

(2012). Site do Projeto UCA Unicamp. Available in: www.nied.unicamp.br/ucaunicamp.

Accessed in: March 2012.

WindschitL, M.;

SahL, K. (2002) Tracing teachers’ use of technology in a laptop computer

school: The interplay of teacher beliefs, social dynamics, and institutional

culture. American Educational Research Journal, 39(1), 165–205.